Joyce ohne Grenzen

Der Bloomsday zwischen Spektakel und Posthumanismus

Am 16. Juni 1954 versammelten sich in Dublin einige trinkfreudige Wortwerker zu einem Ausflug nach Sandymount zum Martello Tower, zu jener Befestigung an der »rotzgrünen Irischen See« also, in der James Joyce das erste Kapitel seines Ein-Tages-Romans »Ulysses« von 1922 ansiedelte. Die Dichter Patrick Kavanagh und John Ryan waren dabei sowie Flann O’Brien. Die Bloomsday-Pilger, so der Dubliner Senator David Norris, hätten auf dem Weg zu ihrem Bestimmungsort an so vielen Pubs Halt machen müssen, dass sie schließlich kaum noch hätten stehen können. Endlich am Turm angekommen, habe das Ganze schließlich darin gegipfelt, dass sich Kavanagh und Flann O’Brien aus Versehen gegenseitig anpinkelten. Norris weiter: »Deswegen muss ich manchmal lachen, wenn die Bloomsday-Veteranen schimpfen, der Bloomsday wäre heutzutage zu einem Massenereignis geworden, das den ›Ulysses‹ vulgarisiert. Ich meine, was wir heute machen, ist doch kaum so vulgär wie der Bloomsday im Jahr 1954.«

In der Tat, dasselbe Dublin, dem Joyce im Jahre 1904 aus Überdruss an der »Stadt des Versagens, der Ranküne und der Unglückseligkeit« den Rücken kehrte, begeht den 16. Juni, an dem die Romanhandlung spielt, mit edwardianischem Kostümklamauk und karnevaleskem Spektakel. In diesem Jahr soll die Stadt im Mittelpunkt stehen und mit Whiskey- und anderen Führungen erkundet werden, wohin es den jüdischen Jedermann Leopold Bloom, dieses »Riesenroß von einem Außenseiter«, den Protagonisten des tausendseitigen Jahrhundertwerks an jenem 16. Juni 1904 verschlagen hat. Da spielt es auch keine Rolle, dass die Originalschauplätze nahezu alle verschwunden sind, die Stadtplanungsvandalen ganze Arbeit geleistet haben. Zu den diesjährigen Höhepunkten des Dubliner Bloomsday-Spektakulums gehören die Events »Bloomsday Body Painting Jam« und »Bloomsday Blowout Cabaret«. Vor Jahren schon konnten wir in der Irish Times lesen, der Bloomsday sei ein brillantes Marketingdatum, und da Literatur eine Ware sei, spiele es auch keinerlei Rolle, ob man das Werk gelesen habe oder nicht, Hauptsache der Name des Autors werde immer wieder ins Spiel gebracht. Joyce als Marke.

Der Verleger Daniel Brody schrieb im Dezember 1948 an den österreichischen Schri!steller Hermann Broch, dem Joyce geholfen hatte, den Nazis zu entkommen, der »Ulysses« sei trotz seiner Weltberühmtheit nirgends ein Bestseller geworden. »Die Berühmtheit stammt daher, daß die Eingeweihten und die Wissenden sich heimlich zuflüsterten: Ja, der Ulysses! Erst als es ein ö“entlicher Skandal wurde, daß jedermann von Ulysses sprach und kein Mensch ihn gelesen hatte, wurde die Weltberühmtheit von Joyce begründet.«

Weltweit sind Wissende und Eingeweihte mit der professionellen Entschlüsselung dieser ins Universelle gesteigerten Dubliner Odyssee befasst. Zweifellos hat die internationale Joyce-Industrie, ein veritables Dechi“riersyndikat mit uneingeschränkter Deutungshoheit, zu einem besseren Verständnis des Romans beigetragen, zugleich aber den Mythos von dessen Unverständlichkeit mitbefördert. In diesem Jahr tre“en sich die Syndikatszugehörigen vom 12. bis zum 16. Juni beim internationalen James-Joyce-Symposium in Mexiko-Stadt unter dem Motto: »Joyce without Borders«.

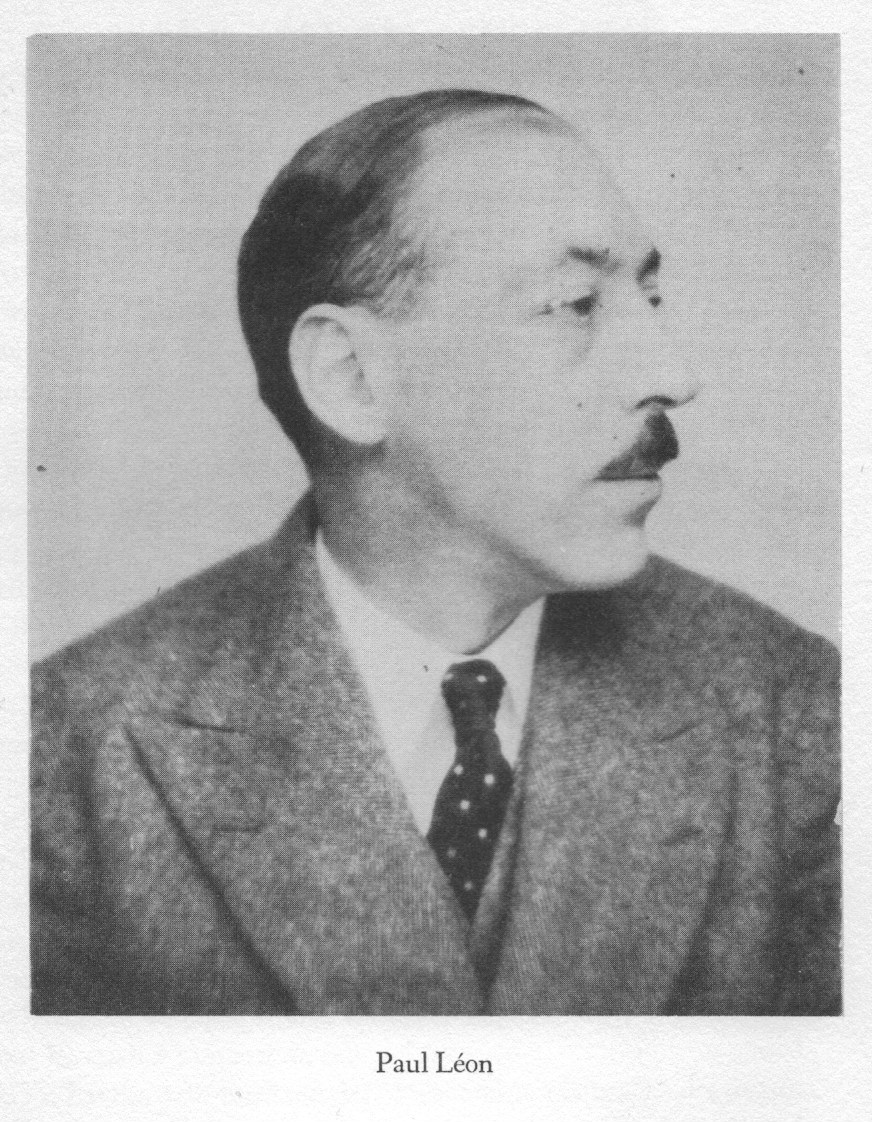

Joyce ohne Grenzen? Nicht gewünscht war aus Gründen der »Kohärenz« ein Vortrag über die SS- Leute, die für den Tod des russischen Juden Paul Léon verantwortlich waren, jenes Freundes von Joyce, der ihm mehr als zehn Jahre lang selbstlos zur Seite gestanden hatte, der im von den Nazis besetzten Paris verha!et und in Auschwitz-Birkenau erschossen wurde. Im Lager Drancy selektierte ihn der SS-Mann Ernst Heinrichsohn, der es nach 1945 zum CSU-Bürgermeister des bayrischen Städtchens Bürgstadt brachte und die Unterstützung seiner CSU-Oberen und der von ihm Regierten auch dann noch genoss, als er 1979 dank der Ermittlungsarbeit von Beate und Serge Klarsfeld in Köln wegen seiner SS-Verbrechen vor Gericht stand.

Neu dür!e sein, dass zu den Joyce-Eingeweihten ein Referent von der US Air Force Academy spricht, von jener Akademie, an der – wie der einstige Academy-Lehrer William J. Astore ausführte – die Studierenden dazu angehalten werden, sich als »Krieger« zu begreifen, als Elite, die den Zivilisten, denen sie recht eigentlich dienen sollen, überlegen ist.

Das internationale Joyce-Symposium findet erstmals in einem Land des Trikont statt. Warum just dort ein Roundtable-Gespräch über den »Ulysses« gleich fünf Akademikern von einer einzigen US- amerikanischen Universität überlassen werden muss, werden die Organisatoren des Symposiums, die nicht müde werden, sich »hohe akademische Standards« zu bescheinigen, gewiss zu erklären wissen. Gleiches gilt wohl dafür, dass nun auch bei einem Joyce-Event der Trans- und Posthumanismus »Aktualität des Möglichen« werden soll. Deren Apologeten erklären den Menschen selbst zum Störfaktor, der als »biologische Entität« überwunden werden müsse. Jürgen Habermas definierte den Transhumanismus als »Weltanschauung einer Sekte«, während der Soziologe Thomas Meyer für eine Verschärfung dieser Definition plädierte: »Der Transhumanismus ist als irre fundamentalistische Wissenscha!ssekte und politische Bewegung (von Intellektuellen) anzusehen, die genauso wenig harmlos ist wie der Sozialdarwinismus früherer Zeiten.«

Der deutsche Romanist Ernst Robert Curtius schrieb 1929, das Joycesche Denken stehe hoch über allen positivistischen Flachheiten. Über den Flachheiten dieser Trans- und Posthumanisten, die eine Biologisierung des Sozialen betreiben, steht es allemal. Mit solchen Frankensteins ist Leopold Blooms Heterotopie von einem »New Bloomusalem« nicht zu verwirklichen.

(https://www.jungewelt.de/artikel/356759.literatur-joyce-ohne-grenzen.html)

Paul Léon and the Career of SS-Heinrichsohn in the Post-Nazi Federal Republic of Germany

Introduction: The wall of indifference to the fate of Paul Léon

Bloomsbury Publishers in London have firmly rejected the essay published below about the death and the murderers of Paul Léon, James Joyce’s friend, who tirelessly worked alongside the Irish writer in Paris for more than ten years.

Paul Léon, a Russian Jew and philosopher, who worked on Benjamin Constant, on Rousseau and for the Archives of Philosophy, was murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Obviously it didn’t matter that my text ›Paul Léon and the Career of SS-Heinrichsohn in the Post-Nazi Federal Republic of Germany‹ is partly based on research in the archives of Auschwitz and Yad Vashem as well as on the correspondence with the International Tracing Service (ITS) — the world’s most extensive archive on victims of Nazi persecution.

If up to now Léon was mentioned in books or essays about Joyce at all we were repeatedly told that he died while being transported to Silesia. Apart from giving the facts concerning his deportation from France to Auschwitz and his execution I reconstructed the career of one of the Nazis who were responsible for Léon’s death – the career of the SS murderer Heinrichsohn.

My essay was intended for a new and annotated edition of the book James Joyce and Paul L. Léon – The Story of a Friendship, written by Léon’s wife under her pen name Lucie Noel and published by The Gotham Book Mart, New York, way back in 1950.

One of the editors of this new edition, Dr. Luca Crispi (University College Dublin), wrote to me that I shouldn’t see this as an act of censorship. »I am sorry to say that Bloomsbury’s Senior Literary Editor is of the opinion that your essay takes the book too far from its main focus on the Joyce-Léon friendship and so has asked us not to include it. (…) This was a firm request by a Senior Literary Editor at Bloomsbury so, obviously, we have to abide by his judgement (…) An editor made a judgement about the flow of the book, that’s all.«

In January Dr. Crispi had written to me, »This is an excellent essay and we would be very pleased if you would allow us to include it in the forthcoming book.«

Paul Léon who was attending to Joyce’s affairs in Nazi occupied Paris got arrested on 21 August 1941. Samuel Beckett had met Léon in the street the previous day and urged him to leave Paris immediately. In her book Lucie Léon (Noel) is vividly describing »a visit« of Gestapo men who were questioning her at length. I wonder if she wasn’t taking it too far from her main focus.

Jürgen Schneider, 27 March 2019

PAUL LÉON, PART II

A few days later I got the following mail:

Dear Jürgen Schneider,

On behalf of the Organizing Committee of Joyce Without Borders, I regret to inform you that your proposed abstracts were not accepted.

This decision was based on the opinions of the Symposium’s Organizing Committee and its Scientific Committee, and has to do with various factors. Among these were the fact that we received an enormous number of proposals, generally of very high academic standards, and from this material, certain themes were emphasized because they gave greater coherence to the organization of the panels and roundtables.

We thank you very much for sending your proposal, and hope you will apply again to participate in future academic activities. (…)

James Ramey, for the Organizing Committee

James Ramey, Full Professor, Department of Humanities

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Cuajimalpa, Mexico City

My reply to Mr. Ramey:

Dear Mr. Ramey,

Thank you for your message.

If I understand it correctly it says that my proposal was of no high academic standards. High academic standards recently led to the strict rejection of my essay on the murderers of Paul Léon by Bloomsbury, London.

It is more than appalling that Paul Léon is commemorated in this dismissive way by academics and scientists of the Joyce community. A very high academic standard indeed – Paul Léon’s murderers would be very grateful.

In an undated note for his biographer, Herbert Gorman, kept in the Special Collections, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, James Joyce wrote about Paul Léon: »The allusion to him should be gr[e]atly amplified. For the last dozen years, in [s]ickness, or health, night and day, he has been an absolutely disinterested and devoted friend. I could never have done what I did without his generous help.«

Have a nice and coherent symposium »Joyce Without Borders«, undisturbed by ugly facts the Joyce industry should long have compiled and presented in the first place.

Jürgen Schneider

My proposals for talks sent to Mexico City were:

#1 James Joyce in Wiesbaden (Hesse, Germany) in April 1930

Although Lucia Joyce (in a letter and in unpublished notes), Paul Léon (quoted in Lucie Noel’s book about the friendship between Léon and Joyce), Stuart Gilbert (in his diary) and Robert Curtius (in an unpublished letter) mentioned the Wiesbaden visit of the Joyce family in April 1930 it more or less went unnoticed by the Joyce community (…)

#2 Paul Léon and the Career of SS-Heinrichsohn in the Post-Nazi Federal Republic of Germany

»This talk will focus on the fate of James Joyce’s friend and tireless helper, the Russian jew Paul Léon, whose selflessness was of another world. It’ll deal with Léon’s arrest in Paris by the Nazis and his stay at the camp of Drancy where he was selected for deportation by the SS-officer Heinrichsohn. Léon was finally shot at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. I have researched the exact circumstances of his deportation and murder in international archives dealing with Nazi crimes. The Joyce literature often falsely says that Léon was murdered while being transported to Silesia.

In the second part the talk will throw a light on the post-war career of Heinrichsohn who became a lawyer and mayor of the Bavarian town Bürgstadt. When he was finally taken to court in 1979 due to the efforts of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld the Bürgstadt citizens still supported him as did leading politicians. Some of these politicians are still around and are still having political influence.«

Instead of replying the Organizing Committee of the Mexican Joyce symposium banned and blocked me from their Facebook page.

***

»Moving the debates back into the academic closet will not revive the ›credibility of scholarship‹.«

–– Julie Sloan Brannon, Who Reads Ulysses?: The Rhetoric of the Joyce Wars and the Common Reader (2003)

Theodor W. Adorno (whose Jewish father converted to Protestantism, while his mother was Catholic) saw Auschwitz as a Zivilisationsbruch – an unprecedented ethical and metaphysical break. The organisers of the JOYCE WITHOUT BORDERS symposium seem to be of the opinion that by ignoring this break and the horrors of history, exemplified by the murder of Paul Léon, they would be achieving »coherence« while in fact their categorical rejection of the findings about Paul Léon’s deportation, his murder and his murderers is nothing but an expression of the repressive continuum.

Furthermore by firmly confirming James Joyce’s appropriation by the academy they are willingly ignoring the fact that Leopold Bloom, Joyce’s protagonist in Ulysses, is a Jewish Everyman embodying an intensely ordinary kind of wisdom and that Ulysses is a novel »written to celebrate ordinary people’s daily rounds« (Declan Kiberd). And last but not least, HCE in Finnegans Wake does not translate into »Here Comes Elitism« but into »Here Comes Everybody« and »Eh? Ha! Check again«.

Jürgen Schneider, May 2019

***

“Paul Léon’s selflessness was of another world.”

Wolfgang Wicht (Sinn und Form, no. 2, 1994)

On 9 May 1977, Ernst Heinrichsohn’s 25th anniversary as a municipal politician was celebrated in the northern Bavarian commune of Bürgstadt (population: 3,600): “The brass band of the Musikverein ‘Germania’ and the ‘Fränkische Rebläuse’ played music, and the former SS man was serenaded by the choirs of the Sängerbund ‘Liederkranz’ and the ‘Singvögel’ from the Lower Main River.” (1)

1/ “Äußerlich dabei”, in Der Spiegel, no. 18, 1979, p. 87. All German language source texts have been translated into English by Hans-Christian Oeser.

The citizens of Bürgstadt were not dissuaded from enjoying themselves by the fact that two months earlier they had learned of the preliminary proceedings which the public prosecutor’s office in Cologne had initiated against CSU mayor Heinrichsohn for aiding and abetting homicide as well as his awareness of plans for the annihilation of the Jewish people in Europe and the meaning of the term ‘final solution of the Jewish question’.

When, in October 1977, the Paris Court of Appeal discussed the case of Klaus Croissant, a German lawyer arrested in France, who had represented prisoners of the Red Army Faction in court in the Federal Republic of Germany, lawyer Serge Klarsfeld warned against Croissant’s extradition “to the Germany of Heinrichsohn” in Le Monde.

I

Ernst Heinrichsohn was born on 13 May 1920 in Berlin-Hermsdorf. After graduating from high school, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, but dismissed in the same year as “unfit for military service”. He was then drafted into the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, Reich Main Security Office), “and was told that, since your name is Heinrichsohn, which sounds similar to Mendelssohn, you will deal with Jewish issues. First, he says, he had to go to the State Library to weed out books by Jewish scholars. […] And he asserts: ‘I was made to put on the uniform of an SS-Unterscharführer. I never was a member of the SS.’” (2)

2/ Rudolf Hirsch, Um die Endlösung : Prozeßberichte, Berlin: Karl Dietz Verlag, 2001, p. 249.

In October 1940, Heinrichsohn was allocated to the Judenreferat (Jewish Department) of the Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des Sicherheitsdienstes (BdS, Commander of the Security Police and the SS Security Service) in Paris under Theodor Dannecker. (3)

3/ Theodor Dannecker, after the war repeatedly described as a pathological “kille.r of Jews”, was born on 27 March 1913 in Tübingen; lawyer; on 20 June joined the SS, six weeks later the NSDAP; since 1937 member of the Judenreferat in the RSHA (together with Eichmann in Department II-112); from 1937 member of the RSHA (together with Eichmann in Department II-112); from 5 September 1940 to September 1942 head of the Gestapo’s Judenreferat in France; subsequently involved in the persecution of Jews in Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia; one of the persons mainly responsible for the extermination of Jews in Hungary; towards the end of the war, responsible for the persecution of Jews in northern Italy; on 10 December 1945 committed suicide in American captivity (cf. Serge Klarsfeld, Dokumentationszentrum für Jüdische Zeitgeschichte CDJC Paris (ed.), Die Endlösung der Judenfrage in Frankreich : Deutsche Dokumente 1941–1944, Paris: Selbstverlag von Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, 1977, p. 233)

Dannecker was answerable to the head of the Security Police in France, Helmut Knochen (4), while receiving his instructions from Adolf Eichmann. Reinhard Heydrich had sent Dannecker to France as a special “Jewish advisor” with the aim of advancing the solution of the “Jewish problem”.

4/ Dr. Helmut Knochen, born on 14 March 1910 in Magdeburg; since 1932 member of the NSDAP and the SA. “On 1 September 1936, at the mediation of Franz Alfred Six, he transferred to the SD as a full-time employee, leaving the SA and joining the SS. After having spent several months at the SD-Oberabschnitt West in Düsseldorf, he joined the SD main office in Berlin in 1937 as head of division. Here he quickly made a career for himself. After the establishment of the RSHA in 1939, he was promoted to Hauptsturmführer, and in the central department “Research on Ideological Opponents” headed by Franz Alfred Six, he was head of the division “Ideological Opponents Abroad”. Knochen had thus arrived in the innermost circle of power and knowledge: In the same year, as Six’s deputy, he attended a meeting in Heydrich’s private apartment where the latter presented the planning of activities for the task forces in Poland. From that day at the latest, Knochen was in full knowledge of the systematic murder of Jews by these mobile units.” (Bernhard Brunner, The France Complex : The National Socialist Crimes in France and the Justice of the Federal Republic of Germany, Frankfurt/Main.: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2007, p. 36) Because of his key role in all measures against Jews in France as commander of the Sipo-SD from 1940 onwards, Knochen was sentenced to death in Paris in 1954, pardoned in 1958 and released to Germany in 1962.

Among Heinrichsohn’s colleagues in Paris were Herbert-Martin Hagen (5), from May 1942 head of Dept. V of the Sipo-SD at the Higher SS and Police Leader in France, and Kurt Paul Werner Lischka (6), head of Office II of the Security Police and the Security Service in Nazi-occupied France. The entire German police apparatus in Paris was in the hands of Kurt Lischka (7).

5/ Herbert-Martin Hagen, born on 20 September 1913 in Neumünster/Holstein; member of the SS since 1 October 1933 (No. 124273); member of the NSDAP (No. 4583139); promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer in 1939, to SS-Sturmbannführer in 1941, and to SS-Obersturmbannführer in 1945; friend and close associate of Eichmann’s in Dept. II-112 of the SD main office and charged with Jewish questions; in June 1940 commander of the Sipo-SD of Bordeaux, where in October 1941 he has all Jews from the surrounding area arrested and names 50 hostages, who are shot immediately; in May 1942 head of Dept. VI of the Sipo-SD at the Higher SS and Police Leader in France; actively involved in the enforcement of all measures against Jews in France and in hostage shootings; in March 1955 sentenced in absentia to life-long forced labor in France (cf. Serge Klarsfeld, loc. cit., p. 234).

6/ Kurt Paul Werner Lischka, born on 16 August 1909 in Breslau, “had studied law and, after passing his second state examination, had entered the service of the Gestapo in Berlin as a probationary judge on 1 September 1935. As early as that he belonged to the SS, membership number 195590, and the Nazi party, membership number 4583185. He quickly made a career for himself: in 1936 he was already promoted to councillor, and in 1938 to head of the Jewish Department of the Gestapo, Dept. II-B4; at the same time he was promoted to SS-Obersturmführer on 20 April 1938. In September of the same year, he became SS-Sturmbannführer. As such, he led the mass arrests of Jews in Berlin during the days following the mass pogrom on 9 November 1938, the so-called Kristallnacht. […] When Heydrich created his Reich Main Security Office, he made Lischka head of Office IV B4, which later organized the mass murder of millions of European Jews under Eichmann. In early 1940, Lischka became head of the Gestapo in Cologne. […] On 1 November 1940 […] he was appointed to the security service and security police of the military commander in France.“ (Friedrich Karl Kaul, Menschen vor Gericht : Ein Pitaval aus unseren Tagen, Berlin [GDR]: Verlag Das Neue Berlin, 1981, p. 181–182) When, in 1961, the Israelis wanted to know from Adolf Eichmann who, in 1939, had founded and headed Dept. IV B4 (responsible for Jewish questions) of the RSHA in Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8, Eichmann answered, »that it was Councillor Kurt Lischka, at the time Theodor Dannecker’s direct superior«. (Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, Erinnerungen, Munich, Berlin, Zurich: 2015, p. 255).

7/ Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, loc. cit., p. 255.

“He was responsible for monitoring the French police; he was also in control of French prisons and internment camps; furthermore, he determined sanctions for ‘atonement persons’, the name chosen for hostages to be shot. Above all, however, Lischka, who was appointed Obersturmbannführer on 1 May 1942, was in charge of the evacuation of Jewish people from France to the extermination camps situated in Poland.” (8)

8/ Friedrich Karl Kaul, loc. cit., p. 182.

Despite his inexperience and youth, Heinrichsohn evolved into an important figure in the Judenreferat in France.

“Chiefly through his function as ‘transport clerk’, he was closely involved in the concrete execution of the murder of Jews. His duties also included supervising the removal of Jews from the Drancy camp.” (9)

9/ Bernhard Brunner, loc. cit., p. 64.

Following a series of attacks against German soldiers on 12 December 1941, the German occupation authorities in Paris arrested 743 Jews as “atonement persons” and interned them in the camps until their deportation. Lischka wrote:

“In the interest of strengthening German authority in the occupied territory, it is urgently necessary to deport as quickly as possible the 1,000 Jews arrested in the course of the action of 12 December 1941. Apart from the fact that the local office and the commander of Greater Paris are harassed with countless petitions for the liberation of these Jews, it must be noted that the French interpret the delay in deportations as German weakness. I therefore ask that special regulations be adopted in this individual case.” (10)

10/ Serge Klarsfeld, Le Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, Paris: Selbstverlag Beate und Serge Klarsfeld, no date given, no page numbers.

Together with Dannecker, Heinrichsohn was one of the two Germans who, at the beginning of July 1942, at the first meeting of the Aktionsausschuss “Weitere Judentransporte aus Frankreich” (Action Committee for Further Transports of Jews from France) with representatives of the French authorities, determined details of the arrest of some 28,000 Jews in Paris, after Dannecker had already discussed the absolute cleansing of the Province with the “Judenreferenten” of the Commanders of the Security Police and the Security Service (Kds) on 30 June 1942, and after Eichmann had come to Paris on 1 July to clarify final matters.

The two noted in their joint minutes “that the speed previously envisaged (3 transports of 1,000 Jews per week) has to be increased significantly within a short period of time, with the aim of the earliest possible and complete cleansing of France of Jews” (11) Dannecker left a detailed note on this meeting under the file number IV J SA 24 and the date 8 July 1942, which states:

11/ Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy – Auschwitz : Die Zusammenarbeit der deutschen und französischen Behörden bei der »Endlösung der Judenfrage« in Frankreich, Nördlingen: Delphi Politik verlegt bei Greno, 1989, pp. 390-391.

“[…] Inspectors of the Prefecture, the anti-Jewish police and female auxiliaries [shall] pull out the relevant filing cards and sort them arrondissement by arrondissement.

After that, Director Hennequin (Police Municipale) shall receive those cards and distribute them to the police commissioners of the arrondissements. These shall have to carry out the arrests according to the cards. […] The Jews are then to be collected in the individual mayor’s offices and subsequently to be transported to the main collection point (Vél[odrôme] d’hiver). Their transport to the individual camps shall be undertaken by the French themselves. […] An age limit of ‘16 to 50 years’ was set.

Children left behind will also be collected at a common place and afterwards taken over by the Union of Jews in France and transferred to children’s homes. […]

It was decided that one transport per week would be started from each camp. […] Thus four trains with 1,000 Jews each will leave the occupied territory every week bound for the east.” (12)

12/ Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy – Auschwitz, loc. cit., pp. 400-402.

On 16 and 17 July, a total of 12,884 Jews, including 4,051 children, were arrested in the Greater Paris area and detained under cruel conditions in the Vélodrôme d’hiver in Paris.

After Dannecker and Heinrichsohn had returned from a “journey through the unoccupied territory – inspection of Jewish camps”, Dannecker informed SS-Unterscharführer Heinrichsohn with a note dated 21 July 1942 (“for SS-Unterscharführer Heinrichsohn’s information and to be filed”):

“On 20 July 1942, Obersturmbannführer Eichmann and SS-Obersturmführer Novak of RSHA IV B 4 called here.

The question of the deportation of children was discussed with SS-Obersturmbannführer Eichmann. He decided that as soon as transport to the Generalgouvernement was possible again, children’s transports could roll. SS-Obersturmführer Novak pledged to make possible by the end of August/beginning of September about 6 transports to the Generalgouvernement, which could contain Jews of all kinds (including Jews unfit for work and elderly Jews).” (13)

13/ Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy – Auschwitz, loc. cit., p. 416.

On 27 August 1942, Heinrichsohn on his own discussed the September programme for the transportation of Jews from unoccupied French territory with the General Delegate of the French police, M. Leguay, and his adjutant, Commandant Sauts. A memo written by Heinrichsohn reads:

“[…] Then the following trains will arrive during the first days of September:

On 1, 2, 3 and 4 September one train each with 1,000 Jews.

At the moment, M. Leguay could not say anything definite about the delivery of the total number of Jews in the September program. […] M. L. promised that he would present himself again in Vichy to make sure that the Jews would only be equipped with the most essential and necessary pieces of luggage when they came to be transported.“

At the end of his memo, Heinrichsohn proudly announced: “On Friday, 28 August 1942, the 25,000th Jew was deported.” (14)

14/ Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy – Auschwitz, loc. cit., pp. 442-443.

II

On 20 August 1941, while police built roadblocks in the 11th arrondissement, Samuel Beckett bumped into Paul Léon on the street in Paris. The two knew each other well. On 2 February 1941, together with Léon’s wife Lucie, with Léon-Paul Fargue and his future wife, Mme. Cheriane, they had celebrated the birthday of James Joyce, who had died a year earlier. (15)

15/ Lucie Noël (i.e. Lucie Léon), James Joyce and Paul L. Léon : The Story of a Friendship, New York, NY: The Gotham Book Mart, 1950, pp. 31-32.

Beckett urged Léon to leave Paris immediately. The latter explained that he could not do so, as his son Alexis was going through the baccalauréat the following day. On 21 August 1941, Paul Léon was arrested and taken to the Drancy camp. For Beckett, this arrest was the decisive factor in joining “Gloria SMH”, a Resistance cell run by the British Special Operations Executive. Beckett later explained to his biographer, James Knowlson: “You just couldn’t watch with your arms crossed.” (16)

16 James Knowlson, “Samuel Beckett’s biographer reveals secrets of the writer’s time as a French Resistance spy”, in The Independent, 23 July 2014.

Léon’s arrest came as no surprise. According to Lucie Léon’s statement to the American Congress, she had been in great danger after narrowly escaping arrest in mid-July 1941. One of Paul Léon’s former students, who was in the Resistance, had warned her that her name was on a list of detainees and deportees. She left her apartment immediately and had to move from one address to another for eight months. (17)

17/ “Relief of Elizabeth Lucie Léon (also known as Lucie Noël), March 4, 1959. Committed to the Committee of the Whole House and Ordered to be printed”, US Congressional Series, 86th Cong., 1st sess., vol. 8, no. 12165, H. Rpt. 175, 6-7, cited in Emilie Morin, Beckett’s Political Imagination, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 158.

Previously, she and her husband had been visited several times by the Gestapo, they had been interrogated at Gestapo headquarters and accused of being spies and hiding British paratroopers. As early as 1940, Paul Léon had anticipated this kind of persecution and handed ownership of their flat over to French friends.

In Drancy, Léon became ill with oedema because of the bad food.

As early as 1946, the physiologist and biochemist Georges Wellers wrote in his book De Drancy à Auschwitz: (18)

18/ The book was published by Éditions du Centre, Paris; cf. Annette Wieviorka / Michel Laffitte, À l’interieur du camp de Drancy, Paris: Perrin, 2012, p. 91. At Heinrichsohn’s order, Pierre Masse was deported to Auschwitz on 30 September 1942, one week after Albert Ulmo, and murdered on arrival. In regard to the conditions prevailing in Royallieu/Compiègne camp cf. the diary excerpts of dentist and professor Benjamin Schatzmann (1877–1942) in Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945, vol. 5: West- und Nordeuropa 1940–Juni 1942. Bearbeitet von Katja Happer, Michael Mayer, Maja Peers. Mitarbeit: Jean-Marc Dreyfus. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag, 2012, pp. 788-794.

“Dannecker arrived at the camp on 12 December at about 6 p.m. Immediately, all inmates were ordered to the yard along with their belongings. Nervous policemen beat panicked people with fists or kicked them to the ground, rushing them all and causing terrible turmoil. When everyone was gathered in the yard, Dannecker selected 300 people, who were immediately removed from the camp along with their belongings. After the first shock has subsided, a depressed mood spread throughout the camp. The 300 selected, so the general agreement, were hostages who would have to pay with their lives for the fact that America had announced its entry into the war on the evening of 11 December.

Two days later, on Sunday, 14 December, around 10 a.m., a Wehrmacht detachment appeared in the camp with a list of 50 names. However, only 47 of the 50 were still in the camp; the missing three had either previously been discharged as seriously ill or had died. The 47 persons present were taken away by the Germans along with their belongings.

In the afternoon of the same day, Dannecker and Unterscharführer Heinrichsohn appeared with several SS men and took a further dozen prisoners with them, whom they regarded as ‘important persons’. Among them were the lawyers Pierre Masse, Albert Ulmo and Paul Léon.

Only much later did we learn that the 300 prisoners and the dozen ‘important persons’ were not shot, but were taken to Compiègne, along with 750 other French Jews arrested in Paris. The fate of most of those proved to be not much better. Those who did not die of cold or hunger in Compiègne were deported on 27 March 1942 and, save four or five people, died in Auschwitz. A few elderly people returned to Drancy on 19 March 1942 and were deported in 1942-43.”

A request initiated by James Joyce’s son Giorgio for the Irish government to intercede in Berlin on behalf of Paul Léon was denied. The Irish chargé d’affaires in Berlin, William Warnock, had initially been asked by the Dublin government to intervene if there was any danger of Léon being shot. Warnock claimed, however, that such an intervention could impair Ireland’s “good relations” with Nazi Germany. The official response was: „No action possible.” (19)

19/ cf. Cian Ó hÉigeartaigh, “Léon’s last letters”, in The Irish Times, 4 April 1992, p. 5.

Paul Léon was one of the prisoners deported from Compiègne to Auschwitz-Birkenau on 27 March 1942. Georges Wellers reports that “‘Sonderführer’ Kuntze” appeared in the camp that day at 2 p.m. with some Germans and a green dossier and by 4 p.m. had selected the persons to be deported. (20)

20/ cf. Georges Wellers in Le Monde Juif, no. 53, March 1952, cited in Serge Klarsfeld, Le Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France.

On that day, 1,112 men were deported from Compiègne and Drancy. They were given the numbers 27533 to 28644. (21)

21/ According to Serge Klarsfeld, a list compiled by the German occupiers with the names of the persons deported to Auschwitz with the first transport was never found. (cf. Serge Klarsfeld, Le Calendrier de la persécution des juifs de France 1940-1944. 1er Juillet–31 août 1942, Paris: Fayard, 2001, p. 345) Klarsfeld’s dossier Le Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France contains a “Liste alphabétique du convoi No. 1”, which lists Paul Léon under the name “LEEN” und gives “25.04.93” as his date of birth; cf. entry Paul Leen on website http://bdi.memorialdelashoah.org/.

It was the first transport of Jews from France to the extermination camps. Lucie and Alexis Léon witnessed Paul Léon’s deportation. The son later reported:

“My mother and I saw him for the last time in Compiègne just before he was due to get on the train. It was like something out of Dante’s Inferno, all those ghostly men. He had to be supported by two people, he was so ill. My mother broke through the German military police cordon and gave him food, but she was pushed back almost immediately. Then we went to the other side of the station and waved through an opening in the fence. Then we couldn’t see him any more because one of the cattle trucks came up.” (22)

22/ cited in “In memory of true friendship”, in The Irish Times, 29 October 1998.

On the same day, Dannecker informed the Reich Main Security Office in Berlin by “Teletype Message No. 5229 (urgent)” that the transport train had left Le Bourget-Drancy station near Paris at 5 p.m.: “Transport strength: 1,100 Jews.” (23)

23/ Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945, loc. cit., p. 798.

At its destination in Auschwitz, where the transport arrived on 30th March, “Dannecker was able to see for himself what the real purpose of the Final Solution was and what happened to the Jews who, under the pretext of a labour assignment, were at the mercy of the exterminatory will of the rulers within the universe of the SS concentration camps. Even if the gas chambers did not yet function – it was not until 19 July 1942 that they were used for murdering the Jews of France – the conditions for survival were absolutely inhumane: 80 percent of the deportees of the second transport died within ten weeks, 80 percent of the third transport within seven weeks.” (24)

24/ Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy – Auschwitz, loc. cit., p. 45.

Paul Léon was murdered just a few days after his arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau. After the war, Lucie Léon met a survivor, who told her that Paul had fallen behind during the march to a construction site and was shot because he could not keep up. (25)

25/ cf. “In memory of true friendship‹, loc. cit.

The International Tracing Service (ITS) in Bad Arolsen provided the following information about Léon’s death:

“Professor LEEN / LEON, Paul, born 25 April 1893 in Petersburg, religion: Mosaic, last residing in Paris VII, Rue Casimir Perier 27; was admitted to Auschwitz concentration camp on 27 March 1942 [sic] with a transport from Compiègne-Drancy, prisoner number: 27 897, and died there on 5 April 1942, cited cause of death: cardiac insuffiency due to pulmonary emphysema.” (26)

26/ Communication of the ITS to the author dated 24 January 2017. “Quellenangabe des Digitalen Archivs ITS Bad Arolsen: Teilbestand: 1.1.2.1, Dokument ID: 516668 – Listenmaterial Auschwitz; Teilbestand: 1.1.2.1, Dokument ID: 597583 – Listenmaterial Auschwitz / Sterbeurkunde.”

In Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust in Jerusalem, the following entry for Paul Léon is to be found:

“Surname: Léon, first name: Paul, sex: male, date of birth: 25/04/1893, place of birth: Petersburg, father’s first name: Leopold, mother’s first name: Ida, mother’s maiden name: Rattner, marital status: married, spouse’s first name: Elisabeth, place of residence during the war: Paris, Seine, France, place of death: Auschwitz, Camp, Poland, date of death: 05/04/1942, status according to source: murdered, source: Auschwitz Death Registers, The State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, type of material: list of Jews murdered in Auschwitz, record number: 5378922.” (27)

27/ On 20 January 1989 Léon’s sister-in-law Eugénie Lang-Ponizowski, Zurich, dedicated a memorial page to Paul Léon in Yad Vashem. In a handwritten addendum she wrote that Léon was listed in the Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France in Roglit, Israel, under the name “Paul Lyon”, “deporté convoi 3, en 1942”.

In the Death Books from Auschwitz there is the following entry: “Leon, Paul (25. 4. 1893, Petersburg, 5. 4. 1942) – 4586/1942.” (28)

28/ Sterbebücher von Auschwitz : Fragmente / Death Books from Auschwitz : Remnants / Księgi i zgonów z Auschwitz : Fragmenty, vol. 2: Namensverzeichnis A–L / Index of Names A–L / Indeks nazwisk A–L. Herausgegeben vom Staatlichen Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau / Edited by State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau / Wydawca Państwowe Muzeum Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Munich / New Providence / London / Paris: KG Saur, 1995, p. 711. The number after the date of death refers to the entry of death, which serves to unequivocally identify each document.

In an undated note for his biographer, Herbert Gorman, kept in the Special Collections, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, James Joyce wrote about Paul Léon:

“The allusion to him should be gr[e]atly amplified. For the last dozen years, in [s]ickness, or health, night and day, he has been an absolutely disinterested and devoted friend. I could never have done what I did without his generous help.”

III

From 1943, Heinrichsohn was an associate of the commander of the Security Police, Kurt Lischka. Shortly before the liberation of Paris, Heinrichsohn and other members of the Gestapo IV E 5 murdered the hero of the French Resistance, André Rondenay, known as “Jarry”, as well as four other Resistance fighters in the forest Les Quatre Chênes around Domont, Val-d’Oise. Afterwards, the members of the death squad met in rue des Saussaies in Paris, seat of the Gestapo’s Office IV, “to drink champagne”. (29)

29/ “Danach Champagner”, in Der Spiegel, 11, 1980, p. 121; cf. Matthew Cobb, 11 Days in August : The Liberation of Paris, London: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

After the liberation of Paris, Heinrichsohn went underground until he was arrested by the Americans in June 1945. He was released at Christmas 1946. From 1949 to 1953, he studied law, and in 1956, after completing his preparatory legal service at individual courts, passed the second state examination. On 1 January 1958, he settled in Miltenberg (Bavaria) as a lawyer. In 1952 he took, as a second job, the office of deputy mayor of Bürgstadt, a commune close to Miltenberg, and in 1960 he became first mayor. In 1956 the Christian Social Union sent him to Miltenberg as a member of the district assembly.

On 7 March 1956, Heinrichsohn was sentenced in absentia to death by the military court of Paris, something which did not harm his political or his lawyerly activities in the slightest. This is why Friedrich Karl Kaul wrote of the “Lischka syndrome”:

“If one considers the indecision of the West German judiciary in the case of Kurt Lischka and his accomplices between an obvious obstruction of justice and a kind of cajoling prosecution, one cannot but speak of a political syndrome which the judiciary of the Federal Republic has contracted – evidently incurably so.” (30)

30/ Friedrich Karl Kaul, loc. cit., p. 178. As for the criminal prosecution of Nazi perpetrators in France and in the Federal Republic of Germany cf. Friedrich Karl Kaul, loc. cit., pp. 183-185 and Bernhard Brunner, loc. cit.

The “legally very superfluous treaty” (Kaul) of 2 February 1971, by which France granted the Federal Republic of Germany the right to initiate new criminal proceedings against Germans who, in absentia, were convicted by French military courts of war crimes and of crimes against humanity committed in France, become legally effective as late as 1975. (31)

31/ In 1974 FDP politician Ernst Achenbach had to resign as rapporteur of the Committee for the Franco-German Supplementary Agreement on the Persecution of Nazi Offenders of 2 February 1971, as he had delayed the adoption of this agreement. Achenbach had been a member of the NSDAP since 1937 and from June 1940 to May 1943 served as Embassy Councillor in Paris, after that as Legation Councillor and closest collaborator of Ambassador Otto Abetz; he was jointly responsible for the deportations of Jews. The German government’s intention to nominate him as European Commissioner for the EEC in Brussels in 1970 had to be abandoned following a dossier published by Beate Klarsfeld on Achenbach’s Nazi activities in occupied France.

It is primarily thanks to the tireless work of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld – Serge Klarsfeld’s father was one of the Jewish Nazi victims in France – that Heinrichsohn and his Nazi comrades Lischka and Hagen were brought to justice. In 2015 Beate Klarsfeld declared in a conversation about hunting down Nazis and the Front National:

“For us the most important thing was that we could initiate the Cologne trial against Hagen, Lischka and Heinrichsohn, the main perpetrators of the deportation of Jews from France, and achieve a conviction.” (32)

32/ cited in Eva zum Winkel, “Beate Klarsfeld im Gespräch über das Jagen von Nazis und den Front National : ‘Wir sind sehr besorgt’”, in jungle world, 21 May 2915.

In 1976, when due to Serge Klarsfeld’s initiative Heinrichsohn’s participation in the Holocaust became public, Heinrichsohn made a declaration of honour before the local council that he was not identical with an “agent of the Gestapo” named “Heinrichson” who was wanted in France. This declaration of honour did not fail to make an impact, not only in his local commune, but also in the executive committee of the Christian Social Union, whose general secretary, Edmund Stoiber, did not want to interfere with pending preliminary proceedings by precondemning Heinrichsohn. The Higher Regional Court in Bamberg did not admit as evidence the incriminating documents published by Klarsfeld, and therefore did not withdraw Heinrichsohn’s approbation as a lawyer. On 6 December 1977, the CSU’s local branch in Bürgstadt unanimously reelected Heinrichsohn as mayoral candidate for the local elections (the local Adler inn was filled to capacity), and CSU district chairman Henning Kaul assured his fellow party member of the “solidarity of the district branch”. Heinrichsohn was reelected as mayor with 85 percent of the votes. The rivalling Social Democratic Party had not even nominated an opponent.

In 1979, the 15th Criminal Chamber of the Cologne Regional Court admitted criminal charges against Lischka, Hagen and Heinrichsohn, but not the murder charge in regard to the “atonement persons”, i.e. charges only to the extent that, due to their official positions in Paris, they were significantly involved in the transports to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp organised by the Reich Main Security Office in the period from 1940 to 1943 – transports, which, as far as the participation of the accused was concerned, comprised a total of 73,176 Jewish men, women and children so that, according to the calculations of the prosecution, 49,884 persons were “unlawfully killed out of murderous intent, cruelly, insidiously and out of base motives”. (33)

33/ cf. Friedrich Karl Kaul, loc. cit., p. 232.

The trial took place between 23 October 1979 and 11 February 1980.

Asked by the presiding judge, Dr. Faßbinder, what he was doing in the Judenreferat at Gestapo headquarters in Paris, Heinrichsohn replied: „Making coffee. And I had to serve it. (34)

34/ Rudolf Hirsch, loc. cit., p. 251.

According to Heinrichsohn, he lacked any sense of guilt as he had learned of the murder of the Jews only after the end of the war. He had believed that the deportees would be sent to labour assignments –there had once been a transport of three thousand work boots – and therefore felt morally but not criminally responsible. Although he had been to the Drancy camp, he had never had anything to do with the deportation of children from there. In this respect, he was the victim of a mix-up with “Heinrichson” or, as he later explained, with Dannecker’s successor Ahnert.

The trial showed that he was “an exceedingly ambitious if inexperienced and low-ranking functionary of mass murder who, while zealously fulfilling the tasks assigned to him, did not shrink from sending small children and the sick to Auschwitz.“ (35)

35/ Bernhard Brunner, loc. cit., p. 346.

Witnesses Odette Daltroff-Baticle and Marie Husson, who had taken care of the many orphaned children in Drancy, identified Heinrichsohn in contemporary photographs and gave the lie to his assertion that he was the victim of a case of mistaken identity. They remembered the “Jew expert” especially in connection with the deportation of children. Odette Daltroff-Baticle stated:

“In 1942 and 1943 I was assigned to the children. Every night of the deportation, Heinrichsohn was present; it was surprising to see this handsome young man in his elegant riding habit treating us badly and brutalizing the reluctant children with a degree of pleasure. I think of all the members of the SS he was the most sadistic, because his presence was completely gratuitous, he came for his pleasure.”

Marie Husson stated:

“I can recall precisely the handsome ephebe that he was, when he paraded in his riding habit and never without his whip around our deeply felt fear and our physiological misery. During my stay in the camp, more than 5,000 children, after their parents had been deported, were loaded into cattle wagons and transported to the gas chambers at Auschwitz. I have never been able to forget their pitiful physical condition, nor have I been able to forget the sadism and brutality of SS-Heinrichsohn, who moved around in this nightmare, screaming, terrorising these poor children and also those who, like me, looked after them.” (36)

36/ Serge Klarsfeld (ed.), Die Endlösung der Judenfrage in Frankreich, loc. cit., p. 235.

On 11 February 1980, Judge Dr. Faßbinder announced the verdict:

“The defendants are guilty of accessory to murder. They are sentenced:

1. the defendant Lischka to a term of imprisonment of 10 years,

2. the defendant Hagen to a term of imprisonment of 12 years,

3. the defendant Heinrichsohn to a term of imprisonment of 6 years.”

To the consternation of the prosecutors, the judge could not see any danger of absconding and refused to place the three convicted defendants under detention. However, the prosecution did not want to take the risk that the three, who through their lawyers appealed the judgment, “would soon send a picture postcard from South America”, and therefore applied again for arrest warrants, which were only issued by the Higher Regional Court. In the morning hours of 16 February 1980, all three men were arrested. Heinrichsohn, however, was briefly remanded on bail as the loyal citizens of Bürgstadt had collected a bond of 200,000 Deutschmarks within a very short time.

After the decision of the Higher Regional Court in Cologne of 7 March 1980, however, Heinrichsohn was again taken into custody. He had meanwhile renounced his office as mayor and declared his resignation from the CSU. On 16 July 1981, the Federal Supreme Court confirmed the verdict in its entirety. On 3 June 1982, Heinrichsohn was released prematurely by order of the Higher Regional Court of Bamberg. The Regional Court of Bayreuth had rejected this in March 1982, since the requirement to serve two third of his sentence had not yet been met. In 1987 the remainder of his sentence was remitted. Heinrichsohn, one link in the long chain of perpetrators responsible for Paul Léon’s murder, died peacefully on 29 October 1994 in Goldbach (Lower Franconia).

Translated from German by Hans-Christian Oeser

The author gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Kunststiftung NRW.

Afterword

The wall of indifference to the fate of Paul Léon

Bloomsbury Publishers in London have firmly rejected this essay published about the death and the murderers of Paul Léon, James Joyce’s friend, who tirelessly acted alongside the Irish writer in Paris for more than ten years.

Paul Léon, a Russian Jew and philosopher, who worked on Benjamin Constant, on Rousseau and for the Archives of Philosophy, was murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Obviously it didn’t matter that my text ›Paul Léon and the Career of SS-Heinrichsohn in the Post-Nazi Federal Republic of Germany‹ is partly based on research in the archives of Auschwitz and Yad Vashem as well as on the correspondence with the International Tracing Service (ITS) — the world’s most extensive archive on victims of Nazi persecution.

If up to now Léon was mentioned at all in books or essays about Joyce we were repeatedly told that he died while being transported to Silesia. Apart from giving the facts concerning his deportation from France to Auschwitz and his execution I reconstructed the career of one of the Nazis who were responsible for Léon’s death – the career of the SS murderer Heinrichsohn.

My essay was intended for a new and annotated edition of the book James Joyce and Paul L. Léon – The Story of a Friendship, written by Léon’s wife under her pen name Lucie Noel and published by The Gotham Book Mart, New York, way back in 1950.

One of the editors of the new edition, Dr. Luca Crispi (University College Dublin), wrote to me that I shouldn’t see this as an act of censorship. »I am sorry to say that Bloomsbury’s Senior Literary Editor is of the opinion that your essay takes the book too far from its main focus on the Joyce-Léon friendship and so has asked us not to include it. (…) This was a firm request by a Senior Literary Editor at

Bloomsbury so, obviously, we have to abide by his judgement (…) An editor made a judgement about the flow of the book, that’s all.«

In January Dr. Crispi had written to me, »This is an excellent essay and we would be very pleased if you would allow us to include it in the forthcoming book.«

Paul Léon who was attending to Joyce’s affairs in Nazi occupied Paris got arrested on 21 August 1941. Samuel Beckett had met Léon in the street the previous day and urged him to leave Paris immediately. In her book Lucie Léon (Noel) is vividly describing »a visit« of Gestapo men who were questioning her. I wonder if she wasn’t taking it too far from her main focus.

A few days later I got the following mail:

Dear Jürgen Schneider,

On behalf of the Organizing Committee of Joyce Without Borders, I regret to inform you that your proposed abstracts were not accepted. This decision was based on the opinions of the Symposium’s Organizing Committee and its Scientific Committee, and has to do with various factors. Among these were the fact that we received an enormous number of proposals, generally of very high academic standards, and from this material, certain themes were emphasized because they gave greater coherence to the organization of the panels and roundtables.

We thank you very much for sending your proposal, and hope you will apply again to participate in future academic activities. (…)

James Ramey, for the Organizing Committee

James Ramey, Full Professor, Department of Humanities

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Cuajimalpa, Mexico City

My reply to Mr. Ramey:

Dear Mr. Ramey,

thank you for your message.

If I understand it correctly it says that my proposal was of no high academic standard. High academic standards recently led to the strict rejection of my essay on the murderers of Paul Léon by Bloomsbury, London.

It is more than appalling that Paul Léon is commemorated in this dismissive way by academics and scientists of the Joyce community. A very high academic standard indeed – Paul Léon’s murderers would be very grateful.

In an undated note for his biographer, Herbert Gorman, kept in the Special Collections, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, James Joyce wrote about Paul Léon: »The allusion to him should be gr[e]atly amplified. For the last dozen years, in [s]ickness, or health, night and day, he has been an absolutely disinterested and devoted friend. I could never have done what I did without his generous help.«

Have a nice and coherent symposium »Joyce Without Borders«, undisturbed by ugly facts the Joyce industry should long have compiled and presented in the first place.

My proposals for talks sent to Mexico City were:

#1 James Joyce in Wiesbaden (Hesse, Germany) in April 1930

Although Lucia Joyce (in a letter and in unpublished notes), Paul Léon (quoted in Lucie Noel’s book about the friendship between Léon and Joyce), Stuart Gilbert (in his diary) and Robert Curtius (in an unpublished letter) mentioned the Wiesbaden visit of the Joyce family in April 1930 it more or less went unnoticed by the Joyce community (…)

#2 Paul Léon and the Career of SS-Heinrichsohn in the Post-Nazi Federal Republic of Germany

»This talk will focus on the fate of James Joyce’s friend and tireless helper, the Russian jew Paul Léon, whose selflessness was of another world. It’ll deal with Léon’s arrest in Paris by the Nazis and his stay at the camp of Drancy where he was selected for deportation by the SS- officer Heinrichsohn. Léon was finally shot at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. I have researched the exact circumstances of his deportation and murder in international archives dealing with Nazi crimes. The Joyce literature often falsely says that Léon was murdered while being transported to Silesia.

In the second part the talk will throw a light on the post-war career of Heinrichsohn who became a lawyer and mayor of the Bavarian town Bürgstadt. When he was finally taken to court in 1979 due to the efforts of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld the Bürgstadt citizens still supported him as did leading politicians. Some of these politicians are still around and are still having political influence.«

Instead of replying the Organizing Committee of the Mexican Joyce symposium banned and blocked me from their Facebook page.

***

Theodor W. Adorno (whose Jewish father converted to Protestantism, while his mother was Catholic) saw Auschwitz as a Zivilisationsbruch – an unprecedented ethical and metaphysical break. The organisers of the JOYCE WITHOUT BORDERS symposium seem to be of the opinion that by ignoring this break and the horrors of history, exemplified by the murder of Paul Léon, they would be achieving »coherence« while in fact their categorical rejection with its claim of »high academic standards« is nothing but an expression of the repressive continuum.

Furthermore by firmly stating that James Joyce belongs to Academia they are willingly ignoring the fact that Bloom, Joyce’s protagonist in Ulysses, is a Jewish Everyman embodying an intensely ordinary kind of wisdom and that Ulysses is a novel »written to celebrate ordinary people’s daily rounds« (Declan Kiberd). And last but not least HCE in Finnegans Wake does not translate into »Here Comes Elitism« but into »Here Comes Everybody« and »Eh? Ha! Check again«.

Jürgen Schneider, May 2019 (corrected March 2020)